Workforce Pell Is Here and Data Readiness Is the Real Test for Credential Innovation

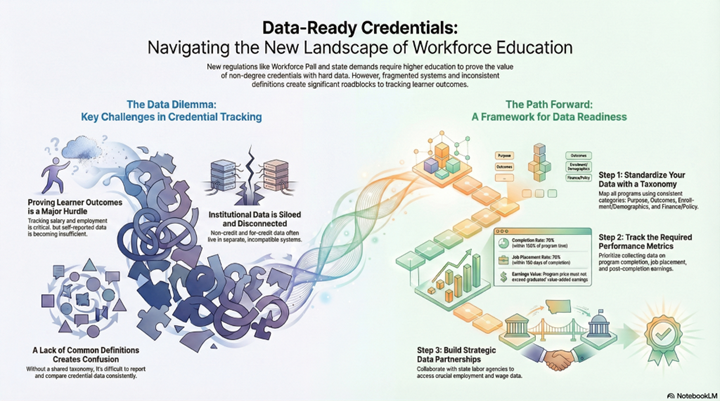

The expansion of Pell Grant eligibility to short-term, non-degree programs—commonly known as Workforce Pell—has become a defining moment for credential innovation. In a strategic conversation hosted by UPCEA in December 2025, higher education leaders made one thing clear: access to Workforce Pell is not primarily a policy challenge. It is a data challenge.

As institutions rush to prepare for Workforce Pell, the conversation revealed both a sense of urgency and a sobering reality. While the opportunity to expand access to federal aid for learners in short-term programs is transformative, many colleges and universities are not yet equipped to meet the data demands that come with it.

Workforce Pell as a Catalyst for Data Urgency

Workforce Pell introduces stringent federal “guardrails” that fundamentally change expectations for non-degree programs. To be eligible, programs must meet specific requirements around length, labor market alignment, credential value, and (most critically) outcomes. Institutions must demonstrate:

- A 70% completion rate

- A 70% job placement rate within 180 days

- Positive earnings outcomes that must exceed published tuition and fee costs

- The above are just a few requirements alongside Workforce Pell’s other program eligibility metrics

These metrics are not aspirational; they are mandatory. As one participant put it, the data required to tap into Workforce Pell funding “will be critical for all of us.” For many institutions, this marks the first time noncredit programs are subject to accountability standards comparable to degree programs.

The Outcomes Data Problem No One Has Solved (Yet)

The most significant barrier to Workforce Pell readiness is outcomes data, especially employment and earnings. Historically, noncredit programs have relied heavily on self-reported alumni surveys. That approach is no longer sufficient.

Leaders agreed that self-reported data will not meet federal verification standards, particularly for earnings. The path forward increasingly points toward integration with State Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS) and federal wage records. While these systems offer more reliable data, they also introduce new complexities, including data-sharing agreements, cross-agency coordination, and the controversial reintroduction of Social Security number collection.

For many institutions, this raises serious concerns about privacy, compliance, and technical capacity. Systems that were never designed to track learners beyond program completion must now support long-term outcomes reporting.

Beyond Metrics: The Challenge of Proving Impact

Even with access to wage data, leaders questioned whether outcomes metrics alone can tell the full story. Proving that a specific credential directly caused a raise, promotion, or job change is inherently difficult. Career trajectories are shaped by many variables, making causality “messy” at best.

Some institutions are experimenting with alternative indicators of success such as job interviews secured, employer engagement, or learner confidence, but these qualitative measures sit uncomfortably alongside federally mandated quantitative metrics. The tension highlights a broader challenge: aligning compliance-driven reporting with learner-centered definitions of success.

Institutional Silos Are the Hidden Risk

Before institutions can report outcomes externally, they must first confront internal fragmentation. A recurring theme was the deep divide between credit and noncredit data systems, which are often entirely disconnected. This separation makes it nearly impossible to create a comprehensive learner record or track stackable credentials over time.

Governance issues compound the problem. As non-degree credentials become more embedded in academic pathways, questions of data ownership (who collects it, manages it, and reports it) are becoming politically charged. Add in third-party providers and online platforms, and visibility into credential activity becomes even more limited and manual.

Underlying all of this is a more fundamental issue: the lack of a shared language. Without consistent definitions and taxonomies for alternative credentials, institutions struggle to align systems, compare outcomes, or tell a coherent story to policymakers and the public.

A System-Level Challenge, Not Just a Campus One

For institutions operating near state borders, outcomes tracking becomes even more complex. Learners may train in one state and work in another, complicating access to wage records and placement data. These realities underscore the need for interstate coordination and stronger data partnerships with workforce agencies, an area where many institutions are just getting started.

Frameworks Pointing the Way Forward

Despite the challenges, the conversation surfaced practical tools that institutions can use to move forward:

- UPCEA’s Workforce Pell Readiness Checklist helps institutions assess readiness across data systems, governance, compliance, and strategy.

- Rutgers’ Noncredit Data Taxonomy 2.0 offers a detailed framework with consistent definitions and more than 90 recommended data elements.

- Credential Engine’s Equity Data Tiers provide a phased approach to publishing data, starting with foundational metrics and building toward next-generation indicators of social mobility.

Together, these resources emphasize that progress is possible but only with intentional planning.

Start Small, Tell the Right Story, Build Coalitions

Perhaps the most important takeaway was philosophical rather than technical. Leaders urged institutions not to be paralyzed by the scale of the challenge. Instead:

- Start with the data you can control.

- Be clear about the story you want your data to tell.

- Build cross-campus coalitions that include registrars, financial aid, workforce leaders, and academic leadership.

- Stay engaged in national conversations as Workforce Pell policy continues to evolve.

Workforce Pell is forcing higher education to confront long-standing gaps in how non-degree learning is defined, tracked, and valued. Institutions that treat this moment as a compliance exercise may struggle. Those that see it as a catalyst for building learner-centered, outcome-driven data systems may emerge stronger and better prepared for the future of credential innovation.

Read the full briefing from the event here.

Julie Uranis, Ph.D., is UPCEA’s Senior Vice President for Online and Strategic Initiatives.

Amy Heitzman, Ph.D., is UPCEA’s Deputy CEO and Chief Learning Officer.

Melissa Peraino is UPCEA’s Director of Content Development and Volunteer Leader Management.

Stacy Chiaramonte is UPCEA’s Senior Vice President of Strategy and Operations for Research and Consulting.

Content for this resource was refined with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model. All text has been thoroughly reviewed, edited, and approved by UPCEA staff with subject matter expertise. References and links have been verified for accuracy and reliability.

Other UPCEA Updates + Blogs

Honoring the Life and Legacy of Dr. Gary W. Matkin

UPCEA joins colleagues, friends, and the broader higher education community in mourning the passing of Dr. Gary W. Matkin, a…

Leading Institutional Transformation in the Age of AI

Artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping work across society, and higher education institutions are no exception. Traditionally, discussions around AI in…