Evaluating Online Teaching: Interviewing Instructors with 10+ Years Experience

We have been discussing online learning efficacy since its inception, with conversations and research focusing on factors such as student outcomes, pedagogy, student support, and community building in online courses and programs. All of these areas of focus are important, as they can point to best practices when designing, developing, and implementing online education. However, I know from personal experience that it takes a lot of time and effort to learn about online teaching and learning… and the field is continually evolving! At most institutions online enterprises were not built in a day, and institutional leaders seeking to build new online enterprises won’t build them any faster. Fundamentally, when online professionals are given adequate resources to grow, online teaching and course design can improve over time and we see growth in the number of online programs and students. One way that institutions can facilitate this progress is through regular online course evaluations. These evaluations can be a means for providing instructors and pedagogical support professionals (e.g. instructional designers) with actionable feedback, and could be used to assess educational quality.

|

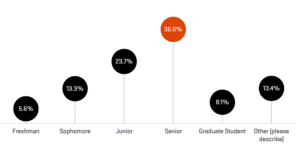

Although online course evaluations could be a used to enhance online learning efficacy, there has been very little discussion or research devoted to inter-departmental online course evaluations. To start this conversation, our research unit analyzed data about inter-departmental online course evaluation from a qualitative study where we interviewed faculty from diverse disciplines who had been teaching online at Oregon State University for 10 years or more. One of the questions we asked these highly experienced online instructors was, “How has online teaching been evaluated at the department level?” Their responses to this question shed light on online teaching evaluation practices during the 2018-19 year in various departments at Oregon State University, as well as potential barriers to online teaching evaluations. We hope that sharing these results can start a broader conversation about best practices for evaluating online teaching in a systematic and useful way. The following is a summary of the results from our analysis, which include two key take-away messages and five questions to consider moving forward:

Key Take-Away #1: The most common methods of online teaching evaluation included student evaluations and peer evaluations. However, participants expressed a lack of clarity regarding best practices for these evaluations.

Student evaluations: In our sample of 33 instructors, almost 2/3 of instructors (20) responded to the question, “How has online teaching been evaluated at the department level?” by mentioning eSET (Electronic Student Evaluation of Teaching) scores. However, several of these instructors identified limitations of student evaluations. For example, one faculty said,

“They (the department) believe that the eSETs are valid and reliable. I don’t believe they are, I disagree with that. They think that you should be able to get the same scores as you do in face to face. It’s not possible. It’s different teaching…the eSETs were not designed for online learning… It’s an invalid assessment of how the instructor is. And I hope they change it.”

While many of the faculty identified the eSETS as one method of online teaching evaluation, their responses suggested that they thought other methods should be used to effectively evaluate online teaching. These responses are consistent with the criticisms that teaching evaluations have received in general higher education (e.g. this link), and are also consistent with comments from faculty in our study who felt that teaching evaluation, regardless of modality, could benefit from clarity about best practices.

Peer evaluations: In addition to discussing student evaluations, almost ½ of instructors interviewed (14) said that their departments conducted online peer evaluations for their online courses. For example, one faculty said, “We have peer observations where faculty go in and observe everybody’s Canvas site and their syllabi, learning outcomes and all of those kinds of things to make sure that we are consistent with what we’re offering on campus and online.” While the faculty who reported this kind of online evaluation generally thought that peer evaluations were a more effective method than student evaluations, some instructors brought up limitations such as:

1. A lack of understanding as to how to evaluate important components of online teaching: While some instructors mentioned sources such as the Quality Matters Rubric, others did not mention any sources. Additionally, others suggested that components other than course design should be evaluated; for example, one faculty said,

“I mean there’s the evaluation of the overall design of the class and sort of the quality controls the campus can bring to bear… QM yeah, so things like that are great but that doesn’t tell you whether any particular teacher’s effective as a communicator with the students.”

These results suggest that we need future conversations in the field in order to elaborate on how to evaluate multiple components of online teaching effectively, including course content, student support, and social presence.

2. Concern regarding whether peer evaluations were constructive: For example, one instructor suggested that some faculty were “overly kind” in their teaching evaluations, because “they don’t want to hurt somebody else’s feelings.” This concern, coupled with the finding that six faculty in the sample suggested that they had only seen online teaching be evaluated when making promotion and tenure decisions, is worth noting. While this was not something that the participants in this study noted, I know that I would give different feedback depending on whether the feedback was going to be used for professional development purposes, or for hiring and tenure decisions. This suggests that departments and institutions need to decide and communicate what the primary purpose of online course evaluations should be. If an institution hopes to leverage course evaluations as a means for professional development, then that goal should be made clear to all involved in the evaluation process. Additionally, institutions might benefit from investing in their feedback culture, as peer evaluators may be hesitant to be constructive in evaluations if constructive feedback is not common within their department, or if they feel like providing constructive feedback could be perceived negatively by their colleagues.

3. Concern regarding the expertise of the peer evaluators: Some instructors suggested that while peer online teaching evaluations had occurred, the evaluators may not have had an appropriate level of expertise in either online education, or the course content area. For example, one faculty described needing to find an evaluator who had online teaching experience, but no understanding of their field. This suggests that ideal peer evaluators would have both an understanding of online teaching, as well as of the content area. However, further discussion in the field could help us consider how evaluators could be selected and supported in order to facilitate optimal feedback.

Key Take-Away #2: Online teaching evaluation depends on multiple stakeholder groups, as practices can vary by leadership and department.

Although all 33 of the faculty interviewed in our study taught online at Oregon State University, the participants varied in their experiences with online teaching evaluations, suggesting that practices can differ by department within the same university. Additionally, some faculty suggested that changes in department leadership had led to changes in course evaluation. For example, one faculty said, “I think again leadership really … Who the person is in charge really defines if that’s happening or not happening.” Additionally, participants suggested that some department chairs were overwhelmed, and suggested that they didn’t think that evaluating online teaching should fall exclusively on department chairs.

These results suggest that online education professionals could focus on disseminating resources, and providing support, to the individual departments. Leaders of these departments may be more likely to prioritize online teaching evaluation if they understand its importance, and view the task as manageable. Future conversations in the field of online higher education could consider methods of facilitating online teaching evaluations, so that ideally evaluations could happen more consistently, within and across institutions.

These results suggest that online education professionals could focus on disseminating resources, and providing support, to the individual departments. Leaders of these departments may be more likely to prioritize online teaching evaluation if they understand its importance, and view the task as manageable. Future conversations in the field of online higher education could consider methods of facilitating online teaching evaluations, so that ideally evaluations could happen more consistently, within and across institutions.

Key Questions to Consider Moving Forward

Overall, instructor responses suggested that there is a lack of clarity regarding comprehensive online teaching evaluation data collection and analysis, as well as a lack of consistency regarding its implementation at one institution. While these study results do not necessarily generalize to other institutions, I think many of the concerns identified by these instructors are useful for the broader field to consider. The following questions are important to consider as we continue the conversation about online teaching evaluation:

- What components of online teaching should be evaluated? How can we effectively measure aspects of online teaching such as course content, student support, and social presence?

- What is the primary purpose of evaluating online teaching? How can this purpose be communicated with instructors and evaluators?

- How can institutions develop a feedback culture that encourages evaluators to provide honest, useful feedback? How could barriers to providing useful feedback be addressed?

- How can currently existing resources on evaluating online teaching be better disseminated to various stakeholder groups (e.g. instructors, department heads)? Could certain resources be condensed or presented in a way that is more digestible for stakeholders?

- How can online learning professionals build systems for online teaching evaluation? How could online learning professionals collaborate with others in order to make evaluations more structured and manageable?

- How do we inform evaluators (both students and faculty members) on the best practices in online teaching so their evaluations detail deviations from best practices rather than carry over expectations from face-to-face instruction?

About

Author

Rebecca Arlene Thomas, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scholar

Ecampus Research Unit, Oregon State University

[email protected]

linkedin.com/in/rebecca-arlene-thomas-7aa82239/

Research Unit

About the Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit: The Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit responds to and forecasts the needs and challenges of the online education field through conducting original research; fostering strategic collaborations; and creating evidence-based resources and tools that contribute to effective online teaching, learning and program administration. The OSU Ecampus Research Unit is part of Oregon State Ecampus, the university’s top-ranked online education provider. Learn more at ecampus.oregonstate.edu/research.

Other UPCEA Updates + Blogs

UPCEA’s Finance Department Grows, Welcomes Tanya Smith

UPCEA proudly welcomes Tanya Smith as the association’s new Controller. Tanya is a Certified Public Accountant with an extensive background…

Read MoreUniversities Investing in Microcredential Leadership (Inside Higher Ed)

Amy Heitzman noticed a new trend when UPCEA, an online and professional education association, put out calls last year to…

Read More