Dive Brief:

- As regulators and industry representatives hash out a potential future for higher education accreditation, particularly rules governing online learning, three industry groups have put forward their own policy recommendations.

- Covering topics such as competency-based education (CBE), regular and substantive interaction and state authorization, the policy briefs were written by the Online Learning Consortium (OLC), the University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA) and the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET).

Briefs Authored by UPCEA, OLC, and WCET Cover Competency-Based Education, Financial Aid, Regular and Substantive Interaction, and State Authorization

WASHINGTON, DC – February 27, 2019 – Today, three organizations in higher education—UPCEA, OLC and WCET—have issued a set of policy briefs relating to necessary changes to federal regulations affecting the professional, continuing, and online education community. These papers address competency-based education, financial aid for the 21st century student, regular and substantive interaction, and state authorization.

The organizations have jointly issued these papers while talks relating to the ongoing rulemaking session are currently underway at the Department of Education to provide additional information to policymakers about the challenges that contemporary learners, and the institutions that serve them, often face. While many of these topics will likely be addressed by the current Department of Education negotiated rulemaking committee, the organizations recognize that others may require Congressional action.

Policymakers interested in a flourishing 21st century workforce must encourage policies that support a 21st century higher education system. Adult learners, and students who engage in online education, can be stifled by outdated policies set up to serve a student population that has not existed for more than 50 years. Through these briefs, the organizations aim to change the conversation around these out-of-date regulations, and together be a stronger voice for innovative and contemporary education policy.

“Higher education institutions provide innovative programs and accessibility to the new normal of adult learners, but antiquated national policies don’t necessarily facilitate greater access to postsecondary learning for today’s students,” said Robert Hansen, CEO of UPCEA. “We hope that these papers will help inform policymakers as we work to expand access and best serve our students.”

“Addressing the needs of the 21st-Century learner includes creating an environment that supports effective use of digital and online learning,” said Kathleen Ives, Executive Director and CEO of the Online Learning Consortium. “Our hope is that our input and our insights are thoughtfully considered as policymakers contemplate the necessary changes for realigning policy with the needs of modern higher education, while addressing inclusion, diversity, equity and access for every student pursuing higher learning.”

Michael Abbiatti, Executive Director of WCET “strongly supports a policy environment that enables and empowers all learner communities to access and receive quality curated digital content and associated credentials in an affordable manner. The current Federal negotiation process must focus on quality assurance in process, content delivery, credentialing, and financial management at all appropriate levels.”

The series of policy briefs is the result of the collaborative efforts of UPCEA, OLC, WCET, and leaders at the member institutions of each organization.

The briefs are structured to inform current talks, as well as inspire solutions around these topics outside of the current negotiated rulemaking session.

You may access the reports here.

# # #

About UPCEA

UPCEA is the leading association for professional, continuing, and online education. Founded in 1915, UPCEA now serves the leading public and private colleges and universities in North America. The association supports its members with innovative conferences and specialty seminars, research and benchmarking information, professional networking opportunities and timely publications. Based in Washington, D.C., UPCEA builds greater awareness of the vital link between adult learners and public policy issues. Learn more at upcea.edu.

About Online Learning Consortium

The Online Learning Consortium (OLC) is a collaborative community of higher education leaders and innovators, dedicated to advancing quality digital teaching and learning experiences designed to reach and engage the modern learner – anyone, anywhere, anytime. OLC inspires innovation and quality through an extensive set of resources, including, best-practice publications, quality benchmarking, leading-edge instruction, community-driven conferences, practitioner-based and empirical research and expert guidance. The growing OLC community includes faculty members, administrators, trainers, instructional designers, and other learning professionals, as well as educational institutions, professional societies and corporate enterprises. Visit http://onlinelearningconsortium.org for more information.

About WCET

WCET (the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies) is the leader in the practice, policy, & advocacy of technology-enhanced learning in higher education. WCET is a national, member-driven, non-profit which brings together colleges, universities, higher education organizations, and companies to collectively improve the quality and reach of technology-enhanced learning programs. Learn more at wcet.wiche.edu

My parents immigrated from China in the 1950s and 60s. They strongly encouraged my brothers and I to study engineering, computers, medicine or mathematics. Nothing else mattered. I chose math and my brothers chose computer science and electrical engineering. I went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in math and a master’s degree in statistics from the University of Vermont. However, the business school would have nothing to do with me…I wasn’t a strong writer.

It took a year of self-study and consuming every writing course at the local community college to prove that I was ready for an MBA. Since then, I’ve grown to appreciate the humanities, the study of history and even reading Harry Potter. Just don’t tell my mother.

Recent research by Strada and Emsi, along with research from UPCEA’s Center for Research and Strategy on the re-positioning or re-engineering the Liberal Arts curriculum for the new economy can be found here.

Many institutional leaders recognize the need for a quality assurance program, yet faculty and staff buy-in to those plans can be elusive. Samford University recently took a collaborative approach to organizational change in its online and professional studies programs, ultimately creating an appetite for quality assurance by increasing awareness, generating buy-in, and empowering faculty through professional development programs. By sharing Samford’s experience and some takeaways from each step in the process, online leaders may use this as a guide to design and execute a plan for quality assurance in online learning.

Step One: Establish a Task Force with a Clear Purpose

When Samford’s online programs hit a growth spurt, the University’s Provost, Dr. Mike Hardin, commissioned a task force to help guide the University’s online efforts. His top priorities — continued academic excellence and faculty professional development. The task force members were strategically identified and included key constituents such as online faculty members, technology support, and disability services personnel, as well as a representative from the university library. The key to the success of the task force was an understanding that its primary purpose was not to identify strategies to grow online programs, but rather to support and reinforce existing programs. This allowed for a collaborative “under the hood” evaluation of technology, faculty development, student services, accreditation standards, and best practices. Ultimately, the task force made several recommendations, including the establishment of a central support office for online programs, the establishment of a multi-layered course recognition policy, and the creation of professional development programs.

Takeaways: For institutions considering quality assurance initiatives, the creation of a working group or task force charged with reviewing online programs and the resources devoted to online learning can yield opportunities for collaboration and critical conversations regarding online program design and quality. Quality standards can include course level design from external entities (Quality Matters) or can be based on internal institution-specific standards. Further, institutional leaders may want to consider program-level (QM Program Certifications) and enterprise-level quality frameworks (Hallmarks of Excellence in Online Leadership).

Step Two: Implement Reasonable Quality Assurance Initiatives

Following the recommendations of Samford’s task force, a newly established “Office of Online & Professional Studies” began the development of a layered course review process. The first step in the process is to meet Samford-specific requirements and a broad application of the Quality Matters (QM) Standards. Then it progresses to a more specific application of the Standards. That’s followed by internal approval and finally QM external recognition. This process allows faculty to move forward with course reviews at a comfortable pace while building their confidence with each stage of recognition. Also critical to this stage was continual assessment and evaluation of the course review process with responsive modifications based on faculty feedback.

Takeaways: Creating a process for quality assurance cannot be done without input from faculty, administrators, and staff. Ultimately, those with knowledge of online pedagogy and design must be involved in the quality assurance efforts for online learning at an institution, either in the design phase or the execution phase of a new plan. Creating a process, with ample feedback opportunities as well as professional development, to familiarize stakeholders with new QA processes are vital components to any new quality assurance initiative.

Step Three: The Creation of Sustainable Professional Development Programs

The final step towards energizing quality assurance in online course design included the creation of relevant and sustainable professional development programs. Samford’s professional development programs were developed based on recommendation by the task force and the assessment of broad faculty need. The faculty development programs were designed to build awareness and empower faculty in the use of varied technology, online pedagogical strategies, and ease into quality assurance processes. A few of the most successful initiatives to date include:

- Lunch & Learns — Samford began by creating a series of Lunch and Learn sessions based on individual Quality Matters Standards. This approach allowed faculty to dig deep into online course quality while taking smaller and more manageable bites of the new quality assurance process without becoming overwhelmed.

- Diversified Professional Development — Samford developed a series of varied professional development opportunities with the intention of appealing to as many faculty as possible. Beyond the Quality Matters Teaching Online Certificate (TOC) program offered, professional development opportunities centered around comprehensive training in the new learning management system (Canvas), sessions in the exploration of online pedagogy, renewed engagement with key national organizations such as UPCEA, and an exclusive four-day course design institute which has provided nearly 50 faculty with resources and support needed to optimize student learning in face-to-face and online courses.

Takeaways: New quality assurance efforts require continuous support and reinforcement until they are recognized as steps within standard operating procedures. As faculty, administrators, and staff see the benefits of these efforts they will become self-sustaining and just another component of online course and program delivery. Creating engaging and focused professional development activities produce new opportunities to engage faculty and create advocates for online learning and the online learning team(s) at the institution.

In conclusion, Samford worked to build a quality assurance process that considered institutional, faculty, administrator, and staff needs. The recommendations of a task force empowered a centralized unit to develop and execute a plan for quality assurance. By adopting an external quality framework widely available to institutions, faculty, administrators, and staff at Samford had confidence in the quality assurance process they designed.

Online leaders would be well advised to consider strategic collaborations with a clear purpose, support from institutional leaders, and continual evaluation and revectoring when needed as these are key components to implementing organizational change and energizing quality assurance in online course design. Further, institutional leaders should consider how course quality, program quality, and enterprise level quality all build towards a continuum of quality in online learning. A discussion of course quality is not the finish line but rather a starting point in terms of quality assurance in online learning.

Marci Johns currently serves as Assistant Provost for Online & Professional Studies and part-time organizational leadership faculty at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. Her list of professional specializations includes working with regulatory and accrediting agencies, leading education technology initiatives, and developing, implementing, and assessing campus-wide strategic plans. Marci holds a J.D. from the Thomas Goode Jones School of Law at Faulkner University, a MA in Public Administration and a BA in history, both from Auburn University Montgomery.

This post was influenced by a Quality Matters article “Creating an Appetite for Quality Assurance in Online Education” which Marci Johns also contributed to.

A centuries-old challenge for teachers has been how to adapt learning materials and presentations to meet the varied backgrounds and abilities of students. Emerging technologies, Ray Schroeder writes, can help meet students where they are and customize learning for them.

From introductory gen-ed classes to advanced graduate seminars, wherever classes online or on campus include more than a couple of students, we have struggled with finding ways to assure that all students are given personalized attention to meet their learning needs.

This has led to differentiated learning models in which students are presented materials based on assessments conducted prior to the class. But that approach too often fails to adapt to progress during the semester and misses opportunities for exchanges and synergies among all learners. It is also most practical only when there are enough classes to support multiple sections at the differentiated levels or multiple groups within a single class.

As expert systems and AI technologies have developed, the promise of personalized learning is now being tested. Matthew Lynch, the “Tech Edvocate,” describes one model:

- First, learning is guided by the interests of the student. Teachers will guide students to select materials, projects and products that reflect student interests.

- Second, students have more choice in virtually every aspect of the process, including where, when and how they learn the material.

- Third, teachers take on the role of coaches instead of the role of information purveyors.

- Fourth, the pace is determined by the learning process of the student.

- Fifth, ed-tech tools are used to manage the multiplicity of learning experiences.

This model utilizes best practices in engaging the learners in class design and adopting materials tied to interests of students. It acknowledges different learning preferences of students. And it uses adaptive learning to accommodate the pace of the students. Managing the adaptive release and assessment utilizes smart technologies.

Georgia Tech’s Commission on Creating the Next in Education notes that:

Based on the successes of these preliminary experiments, the Commission recommends pilot projects on appropriate adaptive learning platforms that could be customized by faculty who would insert the topical content. Some of these experiments may include interactive books and interactive videos, as well as AI agents like “Jill Watson” for many Georgia Tech classes, especially large, remedial, and/or online classes. Some of these adaptive learning platforms can also be transferred to K-12 education as well as many graduate classes (both online and in-person). Pedagogical experiments might be considered that examine where and how this personalized learning is effective. Besides being an integral part of a course, personalized learning modules can be used to support students of varying backgrounds and abilities, or to streamline a curriculum.

We are on the cusp of a new era in which learning is personalized to the needs and interests of the students. With the advent of the lifelong, 60-year learner, we will see more heutagogical approaches to meet the expectations of the self-determined adult learner.

These will require that the learner is adept at designing the learning goals and outcomes. The faculty member will help to guide the learner to relevant resources and suggest paths to reach the desired outcomes.

This may be a far different approach from the standardized lockstep chapter by chapter, weekly quiz and objective final exam of years gone by.

How are you preparing faculty members and students to make the transition to personalized learning? Have you seen expectations shifting from pedagogical approaches to heutagogical practices?

Perhaps this is worthy of a department-wide or college-wide discussion at your institution.

This article was first posted February 6th in Inside Higher Ed’s Inside Digital Learning.

10 Individuals and 6 Programs Receive Association’s Highest Honors

WASHINGTON, February 12, 2019 – UPCEA, the leader in professional, continuing, and online education, has announced the recipients of the 2019 Association Awards. The UPCEA Association Awards program includes recognition of both individual and institutional achievement across the UPCEA membership.

Since 1953, UPCEA has recognized its members’ outstanding contributions to the Association and the field, as well as their achievements in innovative programming, marketing and promotion, community development and services, research and publications, and many other areas.

Award recipients will be honored at the 2019 UPCEA Annual Conference, March 27-29, in Seattle, Wash.

“Serving contemporary learners with innovative and impactful education is at the core of professional, continuing and online education,” said Mary Angela Baker, Director, Center for Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, Salisbury University, and Chair, UPCEA Association Awards Committee. “This year’s award recipients exemplify the breadth and depth of the contributions UPCEA members bring to the field.”

The recipients of this year’s awards are as follows:

Julius M. Nolte Award for Extraordinary Leadership is given to an individual in recognition of unusual and extraordinary contributions to the cause of continuing education on the regional, national, and/or international level.

Recipient: Richard Novak, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Walton S. Bittner Service Citation is given to express appreciation to a member for outstanding service in professional, continuing, and/or online education at his/her institution, and service of major significance to UPCEA.

Recipient: Patrice Miles, Georgia Institute of Technology

Adelle F. Robertson Continuing Professional Educator Award recognizes the scholarship, leadership and contributions to the profession of a person who has entered the field within the past five to ten years.

Recipient: Kim Holka, Oakland University

Phillip E. Frandson Award for Literature recognizes the author and publisher of an outstanding work of continuing higher education literature.

Recipient: Free Range Learning in the Digital Age, Peter Smith

Dorothy Durkin Award for Strategic Innovation in Marketing and/or Enrollment Management recognizes an individual for achievement in strategic planning, marketing innovation or enrollment management success.

Recipient: Steven Kendus, University of Delaware

Leadership in Diversity Award recognizes an individual or a program representing best practices in promoting the educational success of diverse students.

Recipient: Mitchell Springer, Purdue University

Excellence in Teaching Award is presented to individuals who have provided outstanding teaching, course development, mentoring of students, and service to continuing education.

Recipient: Kathy Sherman-Morris, Mississippi State University

Outstanding Professional, Continuing, and/or Online Education Student: Credit Award recognizes outstanding student achievement in professional and continuing education.

Recipient: Stephen Brennan, University of Minnesota

Outstanding Program: Credit Award recognizes outstanding professional and continuing education programs allowing students to earn academic credit.

Recipient: MS Education Learning Design and Technology, Purdue University

Outstanding Program: Noncredit Award recognizes outstanding professional and continuing education programs that do not offer credit.

Recipient: Missouri K-12 ESOL Certification Preparation, University of Missouri-Columbia

UPCEA International Leadership Award recognizes an individual for representing innovative leadership in one or more of the following areas: educational programs and services; administrative practices; collaborations and partnerships; or research.

Recipient: Marissa Lombardi, Education First

UPCEA International Program of Excellence Award recognizes a program engaged in activities that promote the exchange of knowledge and ideas of global significance.

Recipient: The International Psychology Doctorate Online Program, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology

11th Hour Award for Business and Operations is given to an individual, team, or unit in recognition of exemplary character, ethics, and decisive action in times of dire circumstances or emergencies.

Recipient: Independent Learning Transcript Project Team, University of Wisconsin, Continuing Education, Outreach & E-Learning

UPCEA Award for Excellence in Advancing Student Success recognizes an individual or program for advancing the success of students in both credit and non-credit programs.

Recipient: Costas Spirou, Berklee Online

UPCEA Award for Strategic Innovation in Online Education recognizes an institution of higher education that has set and met innovative goals focused on online education and been strategic in the planning, development, implementation and sustainability in the line with the institutional mission.

Recipient: Transforming the Entire University through Innovations in Online Education, University of Arizona

UPCEA Engagement Award recognizes an outstanding mutually-beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources between a UPCEA member institution and one or more external constituents such as local communities, corporations, government organizations, or associations.

Recipients: Center for International Trade & Transportation /POLB Academy of Global Logistics & California State University, Long Beach, College of Continuing & Professional Education

# # #

About UPCEA

UPCEA is the leading association for professional, continuing, and online education. Founded in 1915, UPCEA now serves the leading public and private colleges and universities in North America. The association supports its members with innovative conferences and specialty seminars, research and benchmarking information, professional networking opportunities and timely publications. Based in Washington, D.C., UPCEA builds greater awareness of the vital link between adult learners and public policy issues. Learn more at upcea.edu.

CONTACT:

Molly Nelson, UPCEA Vice President of Communications and Marketing, 202.659.3130, [email protected]

Usually one trend impacts another. If self-driving cars are taking over, then most likely artificial intelligence, data mining, radar technology, and lithium battery development are trending positively. Much of my research this past year focused on Generation Z or iGen (those approximately 16 to 22 years of age) and Millennials. These individuals, along with aging Baby Boomers, are fueling growth of the pet food, pet product, and pet service industry. The pet industry alone in the U.S. was estimated[i] to be over $73 million in expenditures, double the number from 2005, with the average annual cost to own a dog at $1,816[ii].

A recent article showed that, compared to previous generations, many Millennials are putting off having children and raising their pets as their first child[iii]. As a result, the pet food industry has created more nutritious products. With the cost of pet surgeries on the rise and the number of vet visits increasing[iv], insurance companies have created policies and plans for owners insuring their pets, just as they would a human family member.

Similarly, as Millennials increasingly access tech-driven solutions promoting healthy lifestyles like quick access to fresh and nutritious meals, personalized eating plans for food sensitivities, and smart-tech to track physical activity and wellbeing, they’re also investing in emerging pet-care counterpart services like meal delivery services PetPlate and The Farmer’s Dog, PupJoy for tailored treats, and smart trackers FitBark (yes, really) and Toletta.

While no official number exists, the number of emotional support and service animals traveling aboard airlines has increased significantly[v] with nearly 2 million pets, comfort animals, and service animals boarding flights.

With such significant societal changes happening around pets, the question remains, “What role does higher education have in the pet care market?”

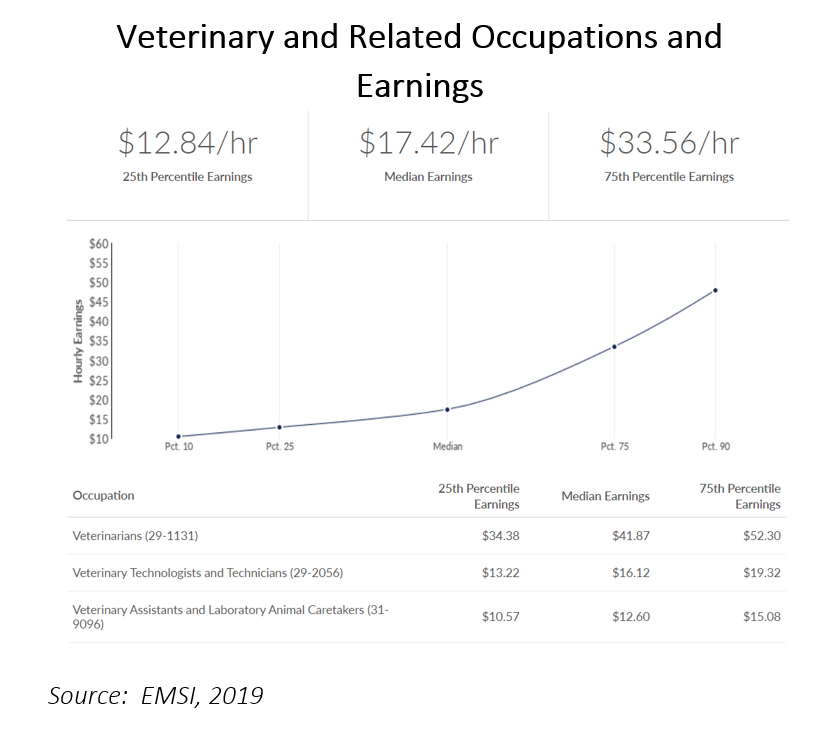

A review of EMSI[vi] data shows the following:

- While average wages are low, the pet care (excluding veterinary) services industry will grow by 34% from 219,148 jobs in 2018 to 293,970 in 2028.

- The field of veterinarians, veterinary technologists and technicians, and veterinary assistants and laboratory animal caretakers pays relatively well and is expected to grow by 20% from 298,484 in 2018 to 358,539 in the next ten years.

- Other occupations such as animal control worker, animal trainer, and animal breeder are expected to grow by 4% and 10% by 2028.

In addition to social sharing businesses such as Uber, Lyft, Airbnb and TaskRabbit, the new economy also has many newer professions that aren’t necessarily officially recorded in labor statistics or job analytics. Many of these jobs are merged in other occupations, such as pet therapy being part of health services, hospice or counseling. Other jobs such as those provided by Wag and Rover dog walking services are often not counted as they are part of the gig economy, where these may be second jobs or non-classified primary occupations.

With societal change being so dramatic regarding pet care and having huge economic impact, the role of higher education could be as follows:

- Review of professions where a degree is required. While many science jobs are expected to grow, colleges and universities need to review supply and demand for degrees related specifically to pet care. In addition, given how connected owners have become with their pets, greater exploration may be needed regarding certification of many other veterinarian-support professions. While no formal degree is required to be a veterinary assistant, training and education are highly encouraged and could serve as a pathway to better employment. Some higher education institutions have also started certificate programs to better train in related professions. Certifications could also be expanded to pet therapy and other highly specialized counselor/therapist niches.

- The health and nutrition of pets may follow an education and credential pathway similar to that for those employed in the food sciences. Many food scientists work within the pet food sector and already require undergraduate or graduate degrees, often in biology, chemistry or food science or processing. However, many seek additional training in various safety, processing, and preparation techniques, some of which are specific to pets.

- Parallels to the health insurance industry could be applied to the pet ownership sector. In fact, over 2.1 million pets were insured in the U.S. and Canada in 2017[vii]. Similar to human populations, data analytics and actuarial sciences can be applied to the health, risk, and death of animals. These techniques used in one sector could be applied to another sector. In addition, the marketing of health insurance or health services to pet owners may also yield new opportunities for higher education.

- Certifications may also be needed in the design and engineering of facilities serving pets or the transportation of pets. There is also greater discussion on college campuses regarding pet-friendly areas and housing. The same is true for public facilities, as well as lodging, especially as iGen and Millennials become more influential in society.

- As pet parents seek ways to care for, and pamper, their pets and incorporate them into their day-to-day lives, universities can consider cross-departmental approaches to related course and program development. Entrepreneurs in the pet care space are applying disciplinary knowledge from engineering, architecture, logistics, psychology, nutrition, interior design, life sciences, hospitality, marketing, and information science.

- While busy professional Millennials seek to provide their pets with care and recreation during the day, Boomers are finding new ways to apply their years of professional wisdom and skills to meet the growing demand. Universities may consider offering related topics in programs for retiring pet-lovers seeking opportunities for flexible, meaningful, active “encore careers.”

- Other opportunities for badging or certification may evolve with the grooming, boarding or even the fashion of pets. New product development or marketing techniques and related training curriculums and programs could be better focused on the pet care products industry.

As author and educator Ana Monnar once said, “Our pets are our family.” Educational systems, degrees and credentials have been built to impact our families, improve the quality of life and address societal problems. As a societal focus increases on one sector over another, colleges and universities have opportunities to pivot their products and services accordingly. The pet care and ownership sector, like many other industries and sectors, will offer greater possibilities for campus-based programs, as well as professional, continuing and online education. It just needs to be researched, understood and developed … or it should be left to the hungrier dogs.

[i] https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp

[ii] Grandstaff, M., “This is how much it really costs to own a dog per year,” USA Today, August 24, 2016.

[iii] Hanbury, M., “Millennials are treating pets like ‘their firstborn child,’ and it’s reportedly causing problems for some of the best-known pet food brands,” BusinessInsider, November 12, 2018

[iv] APPA National Pet Owners Survey, 2017-18

[v] Jansen, B., USA Today, July 16, 2017.

[vi] EMSI, 2019

[vii] The State of the Industry, North American Pet Health Insurance Association, 2018.