Major Updates

- Department of Education Announces Rulemaking and Public Input Period on Multiple Issues

The Biden Administration is moving to leave their mark on higher education, and the first round of regulatory items it is looking at has been released. A public comment period will be followed by a negotiated rulemaking period, for which they will seek nominations of non-federal negotiators like school administrators, experts, and other stakeholders to serve and craft potential regulatory changes. Topics the Department has put on the docket include the following:- Ability to benefit eligibility (mechanism for those without high-school diploma/equivalency to become eligible for federal financial aid)

- Borrower defense to repayment

- Certification procedures for participation in federal financial aid programs

- Change of ownership and change in control of institutions of higher education

- Gainful employment

- Income-contingent loan repayment plans

- Mandatory pre-dispute arbitration and prohibition of class action lawsuit provisions in institutions’ enrollment agreements

- Pell Grant eligibility for prison education programs

- Public service loan forgiveness

- Standards of administrative capability

- Financial responsibility for participating institutions of higher education, such as events that indicate heightened financial risk

- Closed school discharges

- Discharges for borrowers with a total and permanent disability

- Discharges for false certification of student eligibility

The Department noted the need to issue new regulations that “reflect(s) the Department’s commitment to serving students and borrowers well and protecting them from harmful programs and practices that may derail their postsecondary and career goals.” And, that it is “interested in comments on regulations that would address gaps in postsecondary outcomes, such as retention, completion, student loan repayment, and loan default. Specific consideration to disparate impacts by income, race/ethnicity, gender, and other demographic characteristics is encouraged.”

Public hearings will be held on June 21, 23, and 24. More details on how to register for the hearing dates and how to weigh in during the public hearings can be found here. The official public comment submission form is open until July 1, 2021, and can be found here. The Department is also seeking input on suggested items beyond those they have identified to be considered.

UPCEA encourages all of our individual members and member institutions to weigh in and make your voices heard on these topics and others which are important to you and your institution.

- COVID Relief HEERF Eligibility Changed to include DACA, International Students

In an updated FAQ as well as a final rule, the Department of Education has changed the policy of COVID relief funds to now include all students, including DACA and international students. The rule change applies to all three rounds of funding, and applies retroactively to all eligible students. UPCEA was one of many groups calling for this change, and we are very pleased to see it implemented. - Biden to Release FY22 Budget, A Wish List of Administration’s Goals

As we mentioned with the release of the “short” FY22 discretionary budget in April, the full budget requested by the Biden Administration is soon to be released, with some notable items. The $6 trillion budget request largely reflects the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan, focusing on infrastructure and the social safety net, including items like child care. Notably absent from the budget is any support for federal student debt relief. Presidential budget requests rarely pass at the funding levels requested, and are seen as an opening negotiation with congress on how much, and how, the federal budget should be allocated.

Other News

- Distance Education and Innovation Regulations Go Into Effect July 1 (U.S. Department of Education)

- U.S. Department of Education Launches Best Practices Clearinghouse to Highlight Innovative Practices for Reopening Schools and Campuses (U.S. Department of Education)

- Biden Picks Georgetown VP for Education Department General Counsel (Inside Higher Ed)

- Richard Cordray picked by President Biden to be the Chief Operating Officer within the U.S. Department of Education (U.S. Department of Education)

For the past 15 months, colleges and universities have had a difficult time looking beyond the everyday issues on their campuses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Past predictions and forecasts are no longer relevant as a result. To financially survive the pandemic, colleges and universities had to quickly embrace and deploy different technologies, which are the strengths of their professional, continuing and online (PCO) education units (as well as corporate providers) in delivering secure, remote learning. In fact, according to a recent UPCEA survey, 70% of PCO units indicate that they are viewed as more or significantly more valuable to their institutions as a result of the pandemic.

PCO units can help their central administrations look beyond the day-to-day issues and plan for the future, as the disruption of K-12 is likely to create many pathways to learning. The impact on K-12 will create a greater need for safety nets as students earn credentials and ultimately enter the workforce. The lack of readiness of K-12 (no fault of theirs) has created a number of problems and opportunities for higher education, including:

- The pandemic highlighted a myriad of failures in the K-12 system, leaving some students unprepared or unsure of themselves.

- There is talk that some K-12 students may retake courses (or even an entire year) and delay college or entry into the workforce.

- Many academically-unprepared students will be passed on to colleges and universities or directly to employers.

- Some college-ready students may permanently bypass higher education or postpone their education.

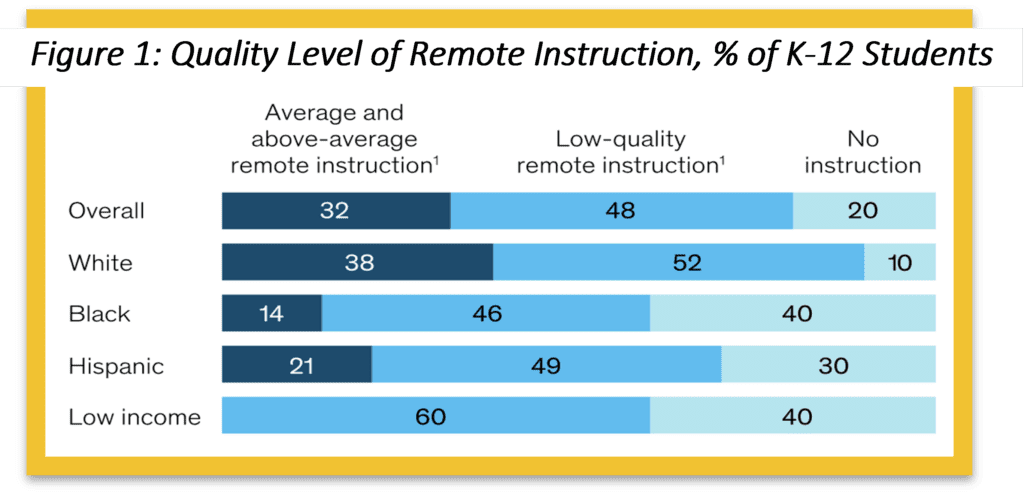

- In general, failures across K-12 have been disproportionate. Figure 1 shows that disproportionate failures have affected low-income and underrepresented students at an exponential rate, compounding existing gaps and persistent achievement disparities.[1]

- This exacerbated a digital divide that will continue to trickle through higher education and enter directly into professional and continuing education units.

With K-12 in flux, traditional students are not as prepared to enter higher education compared to previous years of students; with some experts saying that K-12 students may be up to a full year behind in math.[2] High school juniors and seniors may also be questioning the return on investment for higher education, which will accelerate the popularity of new and nontraditional educational pathways.

With K-12 in flux, traditional students are not as prepared to enter higher education compared to previous years of students; with some experts saying that K-12 students may be up to a full year behind in math.[2] High school juniors and seniors may also be questioning the return on investment for higher education, which will accelerate the popularity of new and nontraditional educational pathways.

Thus, one ‘educational failure’ domino is hitting the next, creating a domino effect that could weaken the education system at large if we don’t act quickly.

In the chaos caused by COVID-19, each state employed a different approach for K-12 public education: some re-opened to in-person classes, some adapted a hybrid system, and some stayed the course with distance education. At the start of 2021, more than 12 million K-12 students were digitally underserved.[3]

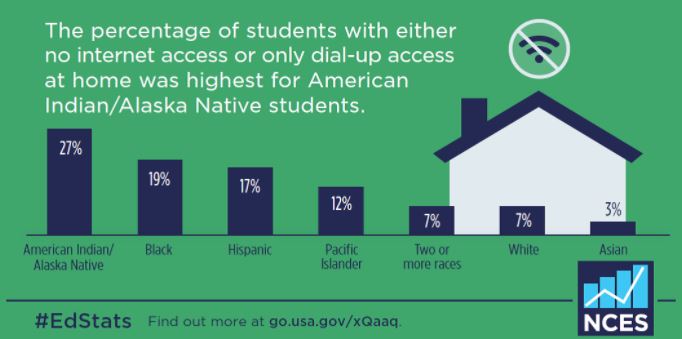

Figure 2: Percentage of Students with No Internet Access | Source: National Center for Education Statistics (7.2020)

The majority of these digitally underserved students come from communities of color and/or low-income households.[4] A report published by McKinsey & Company in 2020 found that “only 60 percent of low-income students are regularly logging into online instruction; 90 percent of high-income students do.”[5] The National Center for Education Statistics reported that Alaska Native and American Indian K-12 students were more likely to have struggled with either no internet access or only dial-up access at home during the pandemic, shown in Figure 2.[6]

Since distance learning was mandated for months in many states, students have already missed a lot of school and are therefore more likely to drop out, especially those who are dependent on the structure and supports of school.[7] Since there is a decrease in education quality and engagement, schools have been forced to lessen graduation requirements, even with the consequences of less skilled students and workers in mind.[8] The weakened high school graduation requirements are causing greater variability in student readiness for college and may even cause an increase in college dropout risks.

These failures ultimately caused the first domino to fall.

The force of this initial domino falling will soon be felt, while we are also just starting to see the signs regarding preparedness and the effects of declining mental health and limited socialization.[9] Looking ahead, I anticipate seven specific ripple effects from the first falling domino.

- We are likely to see an enrollment rollercoaster

Institutions were already grappling with enrollment challenges. The COVID-19 outbreak compounded those challenges as both current and prospective students rethink whether, when, and where they should attend. One potentially false metric in the marketplace is the increase in applications. Colleges and universities have been optimistic that they will survive the pandemic as many have seen increased applications. In the absence of SAT scores as a criteria for acceptance, students applied to more “reach” schools. The demographics of 17 and 18-year-olds does not support an enrollment recovery.

- We are likely to see a surge in demand for online adoption as an alternative

The switch to remote learning has delivered a rapid education – for faculty and students alike – in the technology and design needed for successful online learning. Even if many will be relieved to return to in-classroom learning, the question remains: after the crisis abates, will the lines between “online” and “in-person” be forever blurred? If anything, traditional classroom learners have been immersed in learning online for the past 12-14 months.

- We are seeing widespread financial instability

Increased competition, burgeoning debt and growing compliance costs have created fiscal challenges for many schools. Stimulus funding is but a drop in the bucket of what institutions need to cover their costs associated with COVID-19. Some experts predict that up to 20 percent of institutions are at risk for closure. Many institutions, pre-pandemic, were operating from less than stable financial foundations. When the dust settles for fall enrollments, it is unlikely that finances will improve for these already struggling institutions.

- We will need a more fluid, frictionless, and engaging student experience

Many four-year institutions have relied on physical facilities and amenities to foster student community (i.e., lazy rivers and climbing walls). Now, in order to differentiate, schools must find ways to attract, engage and retain students – digitally. A major criticism of students forced to be online, as opposed to the classroom, was that the instruction wasn’t engaging, exciting or what they paid for. Moving forward, institutions that are able to overcome mundane online instruction by developing new, interactive experiences to learning may see economic stability more rapidly than others.

-

Figure 3: Percentage Change in Common Applications Submitted, 2019-2020, 2020-2021 | Source: Wall Street Journal (3.2021)

We are going to have IT as a critical mission partner and not just an afterthought

IT has enabled staff to work remotely and classes to continue, solidifying its place as a core collaborator in delivering the mission. Connectivity between the institution with students and faculty with students will be foundational to future online education. Investments will be needed to not only create a secure learning environment, but also to improve the learning experience and engagement between different stakeholders.

- We will need to prepare graduates for migration to an elastic workforce

Institutions are learning that successful remote work takes more than technology. It also requires a culture that empowers people to do their jobs remotely and to build the skills they need in this new world of work. Not only will content knowledge be critical in a new economy, but having the skills to work in a flexible environment will be equally important. A new hire would learn the company by being in the office and through mentoring from other staff. These dynamics will change in the new economy.

- Content will change, but so will the credential and dependence on degrees

For the past decade, downward pressure on tuition and rising operating costs have fueled conversations about radically rethinking higher ed business models. That conversation just got louder – and more urgent. What business models are scalable, cost effective and accessible enough to meet the needs of this decade and beyond? The role of business and industry in setting curricular needs is likely to grow. Not only will human resources and a chief online learning officer play a role, but we are likely to see more advisory committees in higher education helping to shape curriculum.There will likely be radical business model transformation. Colleges and universities are going to need to diversify their academic portfolios. Degrees will always play a role, however, alternative credentials and a stackable approach to education are likely to be in higher demand.

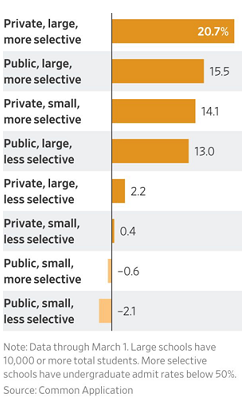

We will soon see how these predictions play out once the dust settles. But these predictions are just the beginning of the fundamental changes expected to ensue. Some higher education institutions may be wary of these ominous predictions after receiving record high applicants this past year. Inside Higher Ed recently reported that newly released data about the Common App show that what has been reported anecdotally in admissions is actually occurring in large numbers.[10] More specifically, the University of Virginia drew a record 48,000 applications for the next class in Charlottesville, about 15 percent more than the year before.[11]

However, despite many institutions receiving a record high number of applicants this past year, and the world beginning its return to “normalcy,” these indicators are misleading. Applications do not necessarily correlate with enrollments. Application increases at elite and large colleges will not translate into higher enrollment numbers. These colleges’ enrollment totals are not growing. Institutions are likely to have less students in the fall and those that do attend are going to be more vulnerable and potentially less ready.

However, this is dichotomous across larger and smaller institutions. Figure 3 shows that larger and more competitive colleges and universities are having a good year and getting lots of applications while smaller and less competitive colleges are not.[12] And first-generation students and those who lack the money to pay for an application are not applying at the same rates they used to. According to an Inside Higher Ed article, “…the [SUNY] system [reported] that [it] had seen an application decline this year of ‘20 percent, one of the largest annual decreases in the system’s 73-year history.’” [13] The growing pains of the pandemic are being felt to varying degrees across the industry, with an increasing burden on non-elite schools.

We are seeing the need to diversify revenues and the ripple effect of the pandemic, as well as the complex demographic coming into play. With less students, many are applying to more, larger schools. Many of these larger schools are seeing a false shadow. On the other hand, many other schools are suffering. We in higher education need to be prepared for this distinction and help these institutions through or we will witness a mass exodus and industry-wide consolidation.

As we enter the post-pandemic period, institutions across all levels should re-evaluate the system failures of the past year to better prepare for what is to come. Higher education is not out of the woods with respect to the pandemic’s spillover effects. Catastrophic shifts will begin to unfold in response to improve the faults made apparent during the pandemic. These paradigms will take years to truly unfold, but these movements have already begun.

As the pandemic caused many of us to pause and reevaluate, millions of students across all levels began to question the value of their education. Students began to consider other options. With rampant financial instability, diminished accessibility, and general pandemic-related uncertainty, cracks were largely exposed in the national education system across all levels. While these cracks were revealed, continuing education units began to expand and capture additional value.

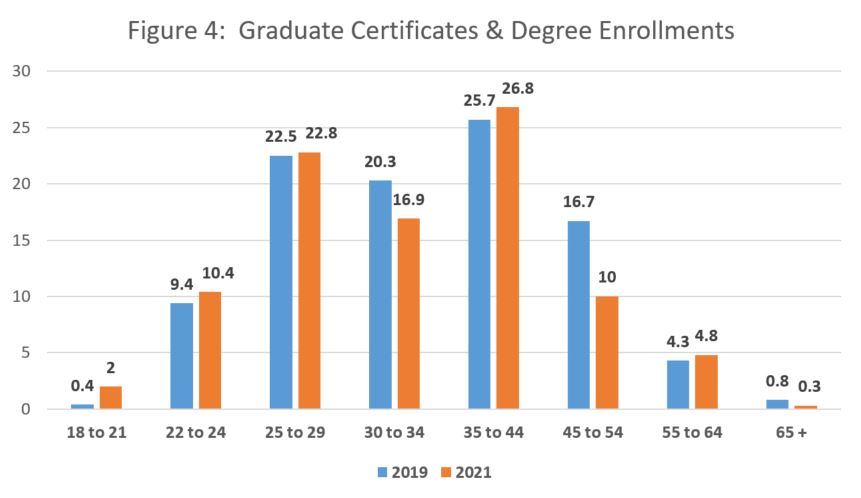

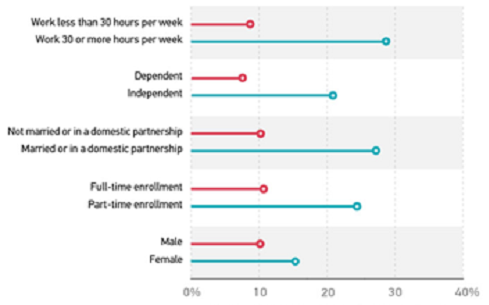

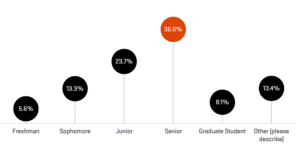

While the pandemic has run its course, and chaos has ensued among higher education institutions, more traditional age undergraduates have been entering PCO channels. InsideTrack and UPCEA have conducted annual surveys to understand enrollment trends. Looking at the 2021 data, traditional age students (18-21) and young people (22-24) are enrolling in graduate certificates and graduate degrees at higher rates this past year than in 2019. This indicates a shift in where enrollment numbers for continuing education units may be coming from and even where enrollments for higher education institutions are shifting towards. The study also found online program satisfaction has decreased slightly from 2019 to 2021. In 2021 68.3 percent are extremely (26.9%) or very (41.4%) satisfied, while that percentage was 73.3 in 2019 (26.8% extremely and 46.5% very).

Source: InsideTrack & UPCEA, 2019 & 2021

Also, in February 2021, individuals from 54 institutions took a brief survey on the effect of the pandemic on their PCO units in 2020 and beyond. Invitations were sent out via UPCEA’s Membership Matters newsletter and a link was also posted on UPCEA’s member community, CORe. As a result of the pandemic, 38 of the 54 respondents (70%) noted that the PCO unit at their institution has become more or much more valuable.

I anticipate PCO units will continue this trajectory as student preferences shift. These units will take on a larger role amongst higher education institutions as the system grapples with how to provide students with high quality education that is increasingly flexible and customizable. The anticipated fallout among the respective K-12 and higher education systems will persist even as the pandemic comes to a close, precipitating the growth of PCO. The spillover effects from the pandemic will continue to be felt and may lead to a rebirth in the role of PCO units.

The hemorrhaging of K-12 and higher education systems has disrupted the quality of education students have received. Because of this breakdown, this generation of students will not be prepared in the same fashion as previous students in their educational journey. This lack of preparation will continue to snowball as students continue their pursuits through the educational food chain. It is anticipated that an increasing number of students will drop out across education levels. Factors such as confidence, financial stability, and self-direction catalyze students to forgo traditional education pathways through K-12 and higher education. Thus, the traditional structure of the education system lacks the adaptability and resources necessary to provide students of all diverse socioeconomic backgrounds with the tools needed to become successful post-grad. As a result, higher education will likely see a re-emergence of baccalaureate degree completion. Given the struggles of K-12 over the past 14 months and potentially longer, some students entering college may drop out and need a place to reconnect. This reconnection could take the form of baccalaureate degree completion later down the road. It will be incumbent upon colleges and universities to regain their own lost students, however, students that drop out may seek a fresh start elsewhere carrying their previously earned credits with them.

PCO units may be leveraged more within higher education institutions to provide students with the assistance they need via modern educational pathways that support student success, even when they fail. Pathways may be developed that leverage non-credit and for-credit opportunities that can feed into each other to keep students on track, even when they face previously insurmountable obstacles. The flexible nature of PCO programming through its online delivery and affordable price-point, align with preferences of younger generations, Generation Z and Millennials, who are becoming a larger segment of PCO enrollments.

Figure 5: Percentage of Students Who Prefer a Mostly or Completely Online Learning Environment | Source: EDUCAUSE (5.2020)

Another potential driver is the “new commuter.” One distinctive feature of traditionally defined commuter students is that they, like traditional adult learners as they are defined, like the face-to-face and had fears of technology and online learning. The pandemic may have been one big, gigantic training session for them. They may go back to the classroom once things settle down, but they may have new confidence or at least a willingness to shop for value. In the least, they have more choices and we have more competition amongst each other. Figure 5 shows that these students have adjusted to learning online and may be opening up more educational opportunities outside traditional options.[14]

In short, a lot of things are happening. Professional programs pre-COVID were gap fillers for progressive job seekers. There was no huge urgency unless you were more self-driven or employer driven. Now things have changed. People have time. Those that are working have less money and want to remain working but know that if another pandemic hits, they want to be better prepared. Higher education may also have reached some scale regarding lower costs, although many more are outsourcing.

It’s not going away, but given the rate of change in the economy and the mindset of young people, it is likely that more pathways will emerge. These dominos or accelerators have and will continue to push the national education system to respond more quickly than ever before. However, the pandemic has sped things up for some and slowed things down for others. We also can choose to be part of the future education mix or start sitting it out.

PCO units will become more strategic to their institutions, bringing more corporate partnerships and technology experiences to the greater campus, but also by creating pathways to K-12 students impacted today by the pandemic. These students are likely to have their own unique challenges as they move in and out of the higher education system and with potential employers.

[1] https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/COVID-19%20and%20student%20learning%20in%20the%20United%20States%20The%20hurt%20could%20last%20a%20lifetime/COVID-19-and-student-learning-in-the-United-States-FINAL.pdf

[2] https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/kids-are-behind-in-math-because-of-covid-19-heres-what-research-says-could-help/2020/12

[3] https://www.bcg.com/press/27january2021-digital-divide-narrowed-must-close-eliminate-risks-students-economy

[4] https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/COVID-19%20and%20student%20learning%20in%20the%20United%20States%20The%20hurt%20could%20last%20a%20lifetime/COVID-19-and-student-learning-in-the-United-States-FINAL.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/the-digital-divide-differences-in-home-internet-access; https://advancingopportunity.org/education/k-12-student-digital-divide-much-larger-than-previously-estimated-and-affects-teachers-too-new-analysis-shows/

[7] https://www.edweek.org/leadership/map-where-are-schools-closed/2020/07

[8] https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/data-how-is-coronavirus-changing-states-graduation-requirements

[9] https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/voices-public-service/7-ways-covid-19-is-accelerating-trends-in-higher-education

[10] https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2021/02/01/full-story-admissions-isnt-just-what-youve-been-reading

[11] https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/harvard-uva-sat-act-requirement-college-applications/2021/01/29/90566562-6176-11eb-9430-e7c77b5b0297_story.html

[12] https://www.wsj.com/articles/college-admission-season-is-crazier-than-ever-that-could-change-who-gets-in-11615909061

[13] https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2021/02/01/full-story-admissions-isnt-just-what-youve-been-reading

[14] https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/5/commuter-students-learning-environment-preferences

The demographic cliff we have been anticipating since the drop in births with the 2008 recession now has a younger sibling — the COVID-19 cliff is coming with another deep drop in recent births.

One of the most common annual refrains I have heard in my decades on the faculty and in administration in higher education has been “Let’s increase the freshman class by 10 percent next fall!”

Motivated by the need to generate more tuition and housing money, universities have looked to increasing the on-campus undergraduate student base. The prospects of such increases are looking dimmer as the “demographic cliff” anticipated by up to a 15 percent drop in freshman prospects approaches, beginning in 2025 due to the decline in birth rate in the 2008 recession and lasting for years after. Those missing babies in 2008 would have begun entering college 17 years later, in 2025.

Now, we see another major drop in births during 2020, with births down 4 percent over the year, but notably accelerating to 8 percent by December as the impact of COVID took hold earlier in the year, reducing births nine months later. It remains to be seen just how long and how significant the decline will be through this year. This new birth drop echo will begin to reach colleges by 2037.

These drops come in the context of a half a dozen years of annual declines in births in the United States. Yet the birth rate is not the only trend threatening higher education as we know it today. There are mounting factors that dissuade prospective students from making a large investment in degrees and instead choosing to go with online alternatives to traditional higher education:

Speaking with The Financial Times, Kirill Pyshkin, senior portfolio manager at Credit Suisse, likened the disruption to what happened in the film industry a few years ago: “This is education’s Netflix moment.” Sean Gallagher, an executive professor of education policy at Northeastern University and founder of Northeastern’s Center for the Future of Higher Education and Talent Strategy, agrees: “This looks to be a catalytic moment. Like what’s happened with the rapid digitization of so many other areas of our daily lives, we’ve probably gained in a few months a level of interest and participation in online education that would have steadily played out over years.”

Meanwhile, Coursera — the large-scale for-profit online degree, certificate and course provider — has posted its earnings from the first quarter. Last year, Coursera reported 70 million learners with more than 200 partners. This year, profits are up more than 70 percent over the first quarter last year, to some $50 million. Meanwhile, Google has announced its massive new Career Certificates in an array of fields, with costs starting at as little as $39 per month. Microsoft and, of course, LinkedIn also are leading providers of professional certifications.

A Strada Education Network COVID-19 Work and Education Survey found that one in four Americans plan to enroll in an education program in the next six months, and they also expressed a preference for nondegree programs, skills training and online options. One wonders if these will be hosted by universities.

Workers are not the only ones expressing little interest in four-year degree programs. Increasing numbers of CEOs are dropping the baccalaureate from a requirement for hiring, as you can find described in this interesting LinkedIn news discussion.

In sum, competition is rapidly growing; the pool of “traditional” students is evaporating; employers are dropping degree requirements; and, with student debt now surpassing $1.7 trillion, we all know that families are looking for more cost-effective paths to the knowledge and skills they seek. “The fundamental business model for delivering education is broken,” said Rick Beyer, a senior fellow and practice area lead for mergers and affiliations at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. “The consolidation era started a few years ago. It will continue. We will see more closures.”

What, then, are the bright spots for postsecondary learning?

Online learning tops the list despite some bad press for the hastily put-together remote learning of last year. Adult students, in particular, prefer the flexibility and mobility of online. Enrollment in online programs has continued to increase while overall higher ed enrollments have declined each of the past dozen years.

Institutional course sharing is picking up steam. Increasingly, colleges are seeing enrollments dropping in selected disciplines such as foreign languages and some of the humanities. Sharing faculty and courses with other institutions in similar circumstances can save money while continuing to serve students and potentially preserve an institution.

Certification and credentialing are two areas that offer opportunities for expansion. These shorter-track online opportunities provide career rewards in less time at a lower cost than a degree. There is hope that these programs will attract larger numbers of student desiring reskilling, upskilling and credentialing to enter new fields.

Millions of former students have completed some work toward a degree, but without the diploma, they have nothing of substance to mark their learning accomplishments. A Lumina Foundation grant has funded an initiative to create a “Credentials as You Go” method to provide incremental credentials for progress toward a baccalaureate degree.

Is your institution impervious to these changes? How are your demographics shifting, in the near term and long term based on these trends? What are you doing to meet the learning needs of new groups of adult learners?

This article was originally published in Inside Higher Ed’s Transforming Teaching & Learning blog.

Nontraditional pathways are a big help to adult learners

May 20, 2021 — North American colleges and universities are beginning to recognize the value of non-credit to credit pathways, according to new research by UPCEA (the University Professional and Continuing Education Association) in partnership with MindEdge Learning. But most of these institutions have yet to implement these nontraditional avenues to a college degree.

Non-credit to credit pathways translate non-credit achievements – such as professional certifications or licenses, prior learning assessments, faculty reviews, and military service – into credit toward a degree or credential. With college enrollments dropping, along with public confidence in the value of a college education, non-credit to credit pathways allow students the flexibility to keep their education options open to match their lifestyle.

This phenomenon is still in its infancy. Fewer than half (43%) of surveyed institutions are currently engaged in non-credit to credit pathway activities – and of those that are, the large majority (78%) are only in the exploratory or pilot stage. And among institutions that are looking at pathways, only 13% feel extremely (5%) or very prepared (8%) to begin offering them – suggesting a missed opportunity to provide students with options that would most benefit them.

Nonetheless, many institutions sense the value that these pathways can provide both to students, and to themselves. Among institutions that are engaged in non-credit to credit pathway activities, 93% say they are doing so to help accommodate nontraditional, adult learners. And, because the pathways can enable a wider pool of students to earn a degree, 85% of these institutions believe that offering such pathways will eventually become an economic necessity for them.

“Non-credit to credit pathways will continue to play an even larger role in diversifying institutions’ offerings to appeal to a generation that’s losing confidence in traditional four-year institutions,” said Frank Connolly, director of research at MindEdge Learning. “Leaders at colleges and universities have an opportunity to reach students where they are, to set them up for success in their careers.”

The survey was distributed through direct email invitations as well as through UPCEA’s member community, CORe; it elicited responses from 122 institutions in the United States and Canada. Of the responding institutions, 70% are four-year public institutions and 24% are four-year private institutions; another 3% are community colleges, and 4% categorize themselves as “other”. The majority of responses came from the respective institutions’ continuing education departments.

Breaking away from the traditional ‘currency of learning’

Non-credit to credit pathways represent a break from the traditional “currency” of higher education, the academic credit. As such, they have the potential to help rein in the rising cost of a college degree.

A great deal of recent research has illustrated the depth of public concern about the high cost of college. A survey of 1,012 U.S. college students, conducted earlier this year by College Finance, found high levels of uncertainty, anxiety, stress, and financial pressure. Many students say they are less confident in the value of their college education, and more anxious than ever about its cost.

In that context, many institutions are coming to recognize the value that non-credit to credit pathways provide students. Among institutions in the exploratory or pilot stage, the top reasons for exploring these pathways include:

- To help accommodate nontraditional, adult learners (93%)

- To provide greater access to higher education (83%)

- To provide alternative academic pathways (80%)

- To garner interest in seeking a degree (63%)

- To boost continuing education (CE) enrollments (58%)

An array of challenges

Despite these perceived benefits, 54% of surveyed institutions report that they are not engaged in non-credit to credit pathway development activities. The most frequently cited reasons for this inactivity are a lack of logistical knowledge (44%) and a lack of institutional support (44%).

In addition, 62% of survey respondents in the exploratory or pilot stage report that they have experienced some degree of internal resistance to these pathways. Among the institutions that report resistance, 100% say they have experienced resistance from faculty, and 46% say they have experienced it from the administration as well. The most frequently cited forms of resistance are distrust in the learning outcomes of other programs (35%) and a lack of willingness to change or improve current conditions (30%).

“The pandemic only accelerated what was already happening, a dramatic shift to a new economy. Higher education was banking on the premise that a college degree, whether online or on-campus, would continue to have staying power,” said Jim Fong, UPCEA’s Chief Research Officer and Director of the Center for Research and Strategy. “The new economy is, however, demanding stackable components to get to the degree. The new economy is also measuring learning and experiences regardless of whether they are credit or non-credit. Employers are coming to grips with the fact that a credit is not the only ‘currency’ of learning in this new economy.”

These results dovetail with the findings of a separate snap poll study that UPCEA conducted this past March. That survey of 112 institutions found that only 30% currently offer non-credit to credit pathways, while 60% do not. Among institutions that do not currently offer pathways, the most frequently cited challenges are institutional barriers or systems (31%), gaining faculty buy-in (29%), and developing non-credit to credit transfer evaluation policy (22%).

Among the institutions that currently offer pathways, community colleges are more likely than other institutions to do so. The greatest challenges institutions faced when implementing pathways include developing a non-credit to credit transfer policy (48%), gaining faculty buy-in (22%), and institutional barriers or systems (13%).

Approximately a quarter (26%) of these institutions say they overcame challenges by reviewing their courses and conducting research to aid implementation, while another 26% say they emphasized communication with faculty. One-in-five (22%) say they are still trying to overcome challenges.

The full Non-Credit to Credit Pathways report can be found here, along with case studies and best practices for implementing non-credit to credit pathways at institutions.

Survey Methodology

In total, 374 member institutions received an email invitation to participate in the non-credit to credit pathways study. The survey was also distributed through UPCEA’s member community, CORe. Representatives from 122 institutions responded to the survey between August 4 and September 15, 2020. The margin of error is ±8% at the 95% confidence level. The survey was designed by Dr. Gail Ruhland of St. Cloud State University, Dr. Lynda Wilson of CSU Dominguez Hills, and Dr. Sandra von Doetinchem of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, with guidance from UPCEA’s Center for Research and Strategy.

About UPCEA

UPCEA is the association for professional, continuing, and online education. Founded in 1915, UPCEA now serves most of the leading public and private colleges and universities in North America. With innovative conferences and specialty seminars, research and benchmarking information, professional networking opportunities and timely publications, we support our members’ service of contemporary learners and commitment to quality online education and student success. Based in Washington, D.C., UPCEA builds greater awareness of the vital link between adult learners and public policy issues. Visit www.upcea.edu.

About MindEdge Learning

MindEdge’s mission is to improve the way the world learns. Since its founding in 1988 by Harvard and MIT educators, the company has served some three million learners. With a focus on digital-first learning resources — from academic courseware to professional development courses — MindEdge’s approach to best practices in online education focuses on learners’ needs across the spectrum of higher education, professional development, skills training, and continuing education. MindEdge is based in Waltham, Mass. Find out more at https://www.mindedge.com/.

Media Contact:

Inkhouse (for MindEdge)

[email protected]

In a recent survey, nearly three-quarters of students — 73 percent — said they would prefer to take some of their courses fully online post-pandemic. However, only half of faculty (53 percent) felt the same about teaching online. The fourth and final installment of Cengage‘s Digital Learning Pulse Survey, conducted by Bay View Analytics on behalf of the Online Learning Consortium, WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies, University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA) and Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, polled 1,469 students and 1,286 faculty and administrators across 856 United States institutions about how higher education is changing in the wake of COVID-19.

As the U.S. economy shows signs of emerging from the pandemic, colleges and universities are making decisions about the fall. Professional, continuing and online (PCO) education units also need to make decisions about new programs they were planning to launch pre-pandemic, systems they had budgeted for upgrade, and staffing that they may have postponed. It was clear that PCO units were invaluable to their institutions during the pandemic as can be seen in UPCEA’s February 2021 snap poll where 70% of units surveyed said that they were viewed as much more valuable or more valuable to their institutions. This, coupled with the support provided by strategic outsource partners, was critical.

April’s snap poll showed that almost two-thirds of those surveyed had an outsource partner of any function and of this group, many were using them for marketing, instructional design or enrollment management. One-in-six said they were using them more often as a result of the pandemic, while 81% said there was no change (which suggests a more long-term view beyond the pandemic). Forty-two percent of those outsourcing also said that their corporate partnership was more valuable as a result of the pandemic. The big takeaway is that PCO units were essential for their institutions to ride out the pandemic and outsource relationships helped many institutions to survive, thrive, or maintain a sense of normalcy regarding offering educational opportunities.

With the dust settling and the future become a little more predictable, PCO units now need to reflect on:

- How do they continue to leverage the relationships they created centrally and university/college-wide,

- Can they build bridges between PCO programs and traditional or centralized programs,

- What elements of the PCO portfolio are stronger or weaker for a new economy,

- What programs or changes to existing programs need to happen for a new economy (new credentials, badges, etc.?), and

- Given the race to online and proliferation of online degrees, what does the institution and the PCO unit need to do differently (i.e. more educational on-ramps or off-ramps, pathways, marketing, etc.)?

The Antikythera mechanism is an astounding device dating to antiquity. It has been hailed as the first mechanical computer, but more precisely it is an educational device.

Let me begin by admitting my lifelong inability to sleep through the night. And, while I am at it, I may as well admit that for the past 25 years I have turned to the internet (against the advice of sleep experts) when I awaken in the early-morning hours. As it happens, last week I had a great discussion with a brilliant ed-tech innovator about current and emerging technologies. That night, I awoke at 2:00 a.m., as often happens. I browsed YouTube to find a lecture to watch. And that is where I came across what is perhaps the most fantastic ancient teaching technology.

I had heard about the Antikythera mechanism a couple of decades ago. I knew it was an early computing device that, mysteriously, was 1,000 years or more ahead of its time, dating from before the common era (or BC, if you prefer). But, little did I know that this device is really best described as a technology to facilitate learning.

The video I chose in the early-morning hours was from the Darwin College lecture series at Cambridge, this one titled “Decoding the Heavens.” This truly great lecture about the Antikythera mechanism was by Jo Marchant. I think this lecture may resonate with many in our field, and I encourage you to view the recording on YouTube as time permits. The incomparable Marchant is a former editor at the science journal Nature who has written for The Economist and The Guardian among other publications. She has literally written the book on the Antikythera mechanism, Decoding the Heavens: Solving the Mystery of the World’s First Computer.

In the briefest of description, this device was discovered sunken in an ancient shipwreck in 1900. Only decades later was it cleaned and restored enough from the millennia of sea encrustations to determine what an awesome discovery it was. It included some 30 gear wheels — though no other geared machines seemingly had been invented for more than 1,000 years. Through the 20th century further technologies were employed to reveal and reconstruct the device, and to uncover and translate the inscriptions engraved on the device. The device was incredibly complex and precise in predicting astronomical movements and events.

While the mechanism conducted calendar computations, the data for those computations were available in detailed tables and narratives. One could simply look at a table or chart to get the precise calculations that the machine provides. Why, then, build such an elaborate and innovative device? As remarkable as it is for computing, the purpose of the device — according to Marchant in the lecture — may be have been as an educational technology device.

What a revelation! This was an ed-tech device that was millennia ahead of general adoption. It is that revelation that gives me pause to question, what might be the educational technology in recent history that could be comparable in some more modest way to the Antikythera mechanism? Likely, any such comparison will be to virtual technologies such as apps or software.

Could a modern-day equivalent be found in the advent of the online learning management system that emerged in the 1990s? These have continued to evolve and increasingly encouraged the rise of sophisticated data and analytics in teaching and learning.

Perhaps, instructional design rubrics such as those by Quality Matters may be considered an impactful early breakthrough in advancing online learning. Encompassing a wide range of best practices, these have established models for effective engagement, assessment and delivery of learning.

Despite concerns today with the overuse of conferencing technologies in the pandemic such as Zoom, these synchronous learning technologies have certainly impacted our teaching and learning over the past decade and more.

As we look ahead, perhaps the advent of high-bandwidth, low-latency networks (such as 5G) delivery of live, interactive virtual reality may be the most important educational technology, enabling immersive learning experiences at a distance.

Certainly, the advent of artificial intelligence in ed tech is renewing the entire field. From data analytics to chat bots to a wide array of research and writing assistance, AI is changing the way we discover and learn.

Adaptive learning, fueled by AI, is a great step toward personalizing learning. Having taught for many decades, I found my most challenging task was to simultaneously meet the needs of a wide range of students with each student’s strengths and deficiencies.

Or, maybe, in fact, it is the medium rather than the multitude of educational technology devices and applications that are developed that will go down as the most remarkable ed tech of our time. The internet, growing out of the ARPANET of the late 1960s, may be the singular leading information and educational technology of our times. It is the interconnection of our networks, our devices and our minds that fuel the learning across distances, enabling collaborations that bring about learning and innovations that change the world.

Consider what ed-tech innovation could revolutionize the 21st century. What is now needed to advance learning in a revolutionary way? How can we create a new era of more efficient, effective and lasting learning, and in doing so further revolutionize our culture?

This article was originally published in Inside Higher Ed’s Transforming Teaching & Learning blog.

University of Phoenix receives recognition for a high-quality online education program

WASHINGTON, D.C. (May 6, 2021) — UPCEA, the association for college and university leaders in professional, continuing, and online education, announced today that the University of Phoenix successfully completed the UPCEA Hallmarks of Excellence in Online Leadership Review program, demonstrating consistent excellence throughout its online enterprise.

The UPCEA Hallmarks of Excellence in Online Leadership Review program evaluates seven key aspects of online education enterprises using a rigorous review process and issues digital badges, in partnership with Credly, to qualifying colleges and universities to mark their achievement. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and the University of Wisconsin-Extension have both been previously recognized through the same review process.

“Over the past four years of new ownership and academic leadership, the University of Phoenix has emphasized curricular quality and faculty development that has resulted in remarkable improvements,” said Ray Schroeder, Senior Fellow for UPCEA, and Professor Emeritus / Associate Vice Chancellor for Online Learning, University of Illinois-Springfield. “Implementing the best practices that are represented in the Hallmarks of Excellence in Online Leadership, the university is focused on initiatives that serve students well; challenges faculty to engage in excellence in both their teaching and scholarship; and engages the larger academic community through research, publications and presentations.”

“Participating in a comprehensive review of the UPCEA Hallmarks of Excellence in Online Leadership afforded the university an opportunity to validate what we are already doing and to leverage valuable feedback relative to the seven Hallmarks,” said Peter Cohen, President of University of Phoenix. “Looking under the hood of our distance education enterprise for opportunities to improve student outcomes and the student experience for all students was particularly important to us during the pandemic year. We appreciate UPCEA for their support and recognition and we’re grateful to the UPCEA Review Team for their collegiality, wisdom, validation, and feedback.”

# # #

About UPCEA

UPCEA is the association for professional, continuing, and online education. Founded in 1915, UPCEA now serves the leading public and private colleges and universities in North America. The association supports its members with innovative conferences and specialty seminars, research and benchmarking information, professional networking opportunities and timely publications. Based in Washington, D.C., UPCEA builds greater awareness of the vital link between adult learners and public policy issues. Learn more at upcea.edu.

About University of Phoenix

University of Phoenix is continually innovating to help working adults enhance their careers in a rapidly changing world. Flexible schedules, relevant courses and interactive learning help students more effectively pursue career and personal aspirations while balancing their busy lives. We serve a diverse student population, offering degree programs at select locations across the U.S. as well as online throughout the world. For more information, visit phoenix.edu.

We have been discussing online learning efficacy since its inception, with conversations and research focusing on factors such as student outcomes, pedagogy, student support, and community building in online courses and programs. All of these areas of focus are important, as they can point to best practices when designing, developing, and implementing online education. However, I know from personal experience that it takes a lot of time and effort to learn about online teaching and learning… and the field is continually evolving! At most institutions online enterprises were not built in a day, and institutional leaders seeking to build new online enterprises won’t build them any faster. Fundamentally, when online professionals are given adequate resources to grow, online teaching and course design can improve over time and we see growth in the number of online programs and students. One way that institutions can facilitate this progress is through regular online course evaluations. These evaluations can be a means for providing instructors and pedagogical support professionals (e.g. instructional designers) with actionable feedback, and could be used to assess educational quality.

|

Although online course evaluations could be a used to enhance online learning efficacy, there has been very little discussion or research devoted to inter-departmental online course evaluations. To start this conversation, our research unit analyzed data about inter-departmental online course evaluation from a qualitative study where we interviewed faculty from diverse disciplines who had been teaching online at Oregon State University for 10 years or more. One of the questions we asked these highly experienced online instructors was, “How has online teaching been evaluated at the department level?” Their responses to this question shed light on online teaching evaluation practices during the 2018-19 year in various departments at Oregon State University, as well as potential barriers to online teaching evaluations. We hope that sharing these results can start a broader conversation about best practices for evaluating online teaching in a systematic and useful way. The following is a summary of the results from our analysis, which include two key take-away messages and five questions to consider moving forward:

Key Take-Away #1: The most common methods of online teaching evaluation included student evaluations and peer evaluations. However, participants expressed a lack of clarity regarding best practices for these evaluations.

Student evaluations: In our sample of 33 instructors, almost 2/3 of instructors (20) responded to the question, “How has online teaching been evaluated at the department level?” by mentioning eSET (Electronic Student Evaluation of Teaching) scores. However, several of these instructors identified limitations of student evaluations. For example, one faculty said,

“They (the department) believe that the eSETs are valid and reliable. I don’t believe they are, I disagree with that. They think that you should be able to get the same scores as you do in face to face. It’s not possible. It’s different teaching…the eSETs were not designed for online learning… It’s an invalid assessment of how the instructor is. And I hope they change it.”

While many of the faculty identified the eSETS as one method of online teaching evaluation, their responses suggested that they thought other methods should be used to effectively evaluate online teaching. These responses are consistent with the criticisms that teaching evaluations have received in general higher education (e.g. this link), and are also consistent with comments from faculty in our study who felt that teaching evaluation, regardless of modality, could benefit from clarity about best practices.

Peer evaluations: In addition to discussing student evaluations, almost ½ of instructors interviewed (14) said that their departments conducted online peer evaluations for their online courses. For example, one faculty said, “We have peer observations where faculty go in and observe everybody’s Canvas site and their syllabi, learning outcomes and all of those kinds of things to make sure that we are consistent with what we’re offering on campus and online.” While the faculty who reported this kind of online evaluation generally thought that peer evaluations were a more effective method than student evaluations, some instructors brought up limitations such as:

1. A lack of understanding as to how to evaluate important components of online teaching: While some instructors mentioned sources such as the Quality Matters Rubric, others did not mention any sources. Additionally, others suggested that components other than course design should be evaluated; for example, one faculty said,

“I mean there’s the evaluation of the overall design of the class and sort of the quality controls the campus can bring to bear… QM yeah, so things like that are great but that doesn’t tell you whether any particular teacher’s effective as a communicator with the students.”

These results suggest that we need future conversations in the field in order to elaborate on how to evaluate multiple components of online teaching effectively, including course content, student support, and social presence.

2. Concern regarding whether peer evaluations were constructive: For example, one instructor suggested that some faculty were “overly kind” in their teaching evaluations, because “they don’t want to hurt somebody else’s feelings.” This concern, coupled with the finding that six faculty in the sample suggested that they had only seen online teaching be evaluated when making promotion and tenure decisions, is worth noting. While this was not something that the participants in this study noted, I know that I would give different feedback depending on whether the feedback was going to be used for professional development purposes, or for hiring and tenure decisions. This suggests that departments and institutions need to decide and communicate what the primary purpose of online course evaluations should be. If an institution hopes to leverage course evaluations as a means for professional development, then that goal should be made clear to all involved in the evaluation process. Additionally, institutions might benefit from investing in their feedback culture, as peer evaluators may be hesitant to be constructive in evaluations if constructive feedback is not common within their department, or if they feel like providing constructive feedback could be perceived negatively by their colleagues.

3. Concern regarding the expertise of the peer evaluators: Some instructors suggested that while peer online teaching evaluations had occurred, the evaluators may not have had an appropriate level of expertise in either online education, or the course content area. For example, one faculty described needing to find an evaluator who had online teaching experience, but no understanding of their field. This suggests that ideal peer evaluators would have both an understanding of online teaching, as well as of the content area. However, further discussion in the field could help us consider how evaluators could be selected and supported in order to facilitate optimal feedback.

Key Take-Away #2: Online teaching evaluation depends on multiple stakeholder groups, as practices can vary by leadership and department.

Although all 33 of the faculty interviewed in our study taught online at Oregon State University, the participants varied in their experiences with online teaching evaluations, suggesting that practices can differ by department within the same university. Additionally, some faculty suggested that changes in department leadership had led to changes in course evaluation. For example, one faculty said, “I think again leadership really … Who the person is in charge really defines if that’s happening or not happening.” Additionally, participants suggested that some department chairs were overwhelmed, and suggested that they didn’t think that evaluating online teaching should fall exclusively on department chairs.

These results suggest that online education professionals could focus on disseminating resources, and providing support, to the individual departments. Leaders of these departments may be more likely to prioritize online teaching evaluation if they understand its importance, and view the task as manageable. Future conversations in the field of online higher education could consider methods of facilitating online teaching evaluations, so that ideally evaluations could happen more consistently, within and across institutions.

These results suggest that online education professionals could focus on disseminating resources, and providing support, to the individual departments. Leaders of these departments may be more likely to prioritize online teaching evaluation if they understand its importance, and view the task as manageable. Future conversations in the field of online higher education could consider methods of facilitating online teaching evaluations, so that ideally evaluations could happen more consistently, within and across institutions.

Key Questions to Consider Moving Forward

Overall, instructor responses suggested that there is a lack of clarity regarding comprehensive online teaching evaluation data collection and analysis, as well as a lack of consistency regarding its implementation at one institution. While these study results do not necessarily generalize to other institutions, I think many of the concerns identified by these instructors are useful for the broader field to consider. The following questions are important to consider as we continue the conversation about online teaching evaluation:

- What components of online teaching should be evaluated? How can we effectively measure aspects of online teaching such as course content, student support, and social presence?

- What is the primary purpose of evaluating online teaching? How can this purpose be communicated with instructors and evaluators?

- How can institutions develop a feedback culture that encourages evaluators to provide honest, useful feedback? How could barriers to providing useful feedback be addressed?

- How can currently existing resources on evaluating online teaching be better disseminated to various stakeholder groups (e.g. instructors, department heads)? Could certain resources be condensed or presented in a way that is more digestible for stakeholders?

- How can online learning professionals build systems for online teaching evaluation? How could online learning professionals collaborate with others in order to make evaluations more structured and manageable?

- How do we inform evaluators (both students and faculty members) on the best practices in online teaching so their evaluations detail deviations from best practices rather than carry over expectations from face-to-face instruction?

About

Author

Rebecca Arlene Thomas, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scholar

Ecampus Research Unit, Oregon State University

[email protected]

linkedin.com/in/rebecca-arlene-thomas-7aa82239/

Research Unit

About the Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit: The Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit responds to and forecasts the needs and challenges of the online education field through conducting original research; fostering strategic collaborations; and creating evidence-based resources and tools that contribute to effective online teaching, learning and program administration. The OSU Ecampus Research Unit is part of Oregon State Ecampus, the university’s top-ranked online education provider. Learn more at ecampus.oregonstate.edu/research.